In my first meeting with the Save Darfur Coalition, their executive director told me, “Our mission is to put ourselves out of business.” Normally that would be a red flag coming from any client, but in this case it seemed completely appropriate and sincere. We did our best to help them reach that goal.

In February 2003, violence erupted in the Darfur region of Western Sudan, sparking the first genocide of the 21st century. The Sudanese government began targeting innocent civilian populations with a campaign of rape, torture, and murder. An estimated 400,000 men, women, and children were killed, and more than 2.5 million displaced. A more thorough history of the Darfur conflict can be found here.

In September 2006, the Save Darfur Coalition received a grant for U.S. and international advertising to support its mission of ending the genocide. They hired GMMB to help. We worked closely with the Coalition to develop communications that would raise global awareness of the issue and mobilize the world to help stop the atrocities.

From the start, we decided that the personal stories of this conflict could speak for themselves. We didn’t need to sensationalize anything, we needed only to share these stories with the world. To bring the reality of suffering in Darfur closer to audiences, we developed a campaign that relied on eyewitness accounts from victims and survivors. In television spots, we captured footage of ordinary Americans reading and reacting to these word-for-word testimonials. The spots were broadcast nationally and accompanying print ads featured journalists’ photos and quotes from Darfuri survivors. The ads ran in more than 30 publications and 10 languages in major cities throughout Europe. Outdoor and transit ads ran in Washington, New York, Paris, Brussels, and Berlin. The campaign called on audiences to pressure President Bush and other world leaders to play an active role in bringing peace to Darfur.

Save Darfur determined it was also important to communicate with the Muslim world – specifically to alert people that the victims of Darfur were themselves Muslim. We conducted careful research in the Middle East before developing the work. We then traveled to Europe to produce a TV spot featuring refugees recounting stories in their native Arabic, imploring fellow Muslims for help. This spot ran on major Arabic-language networks throughout the Middle East.

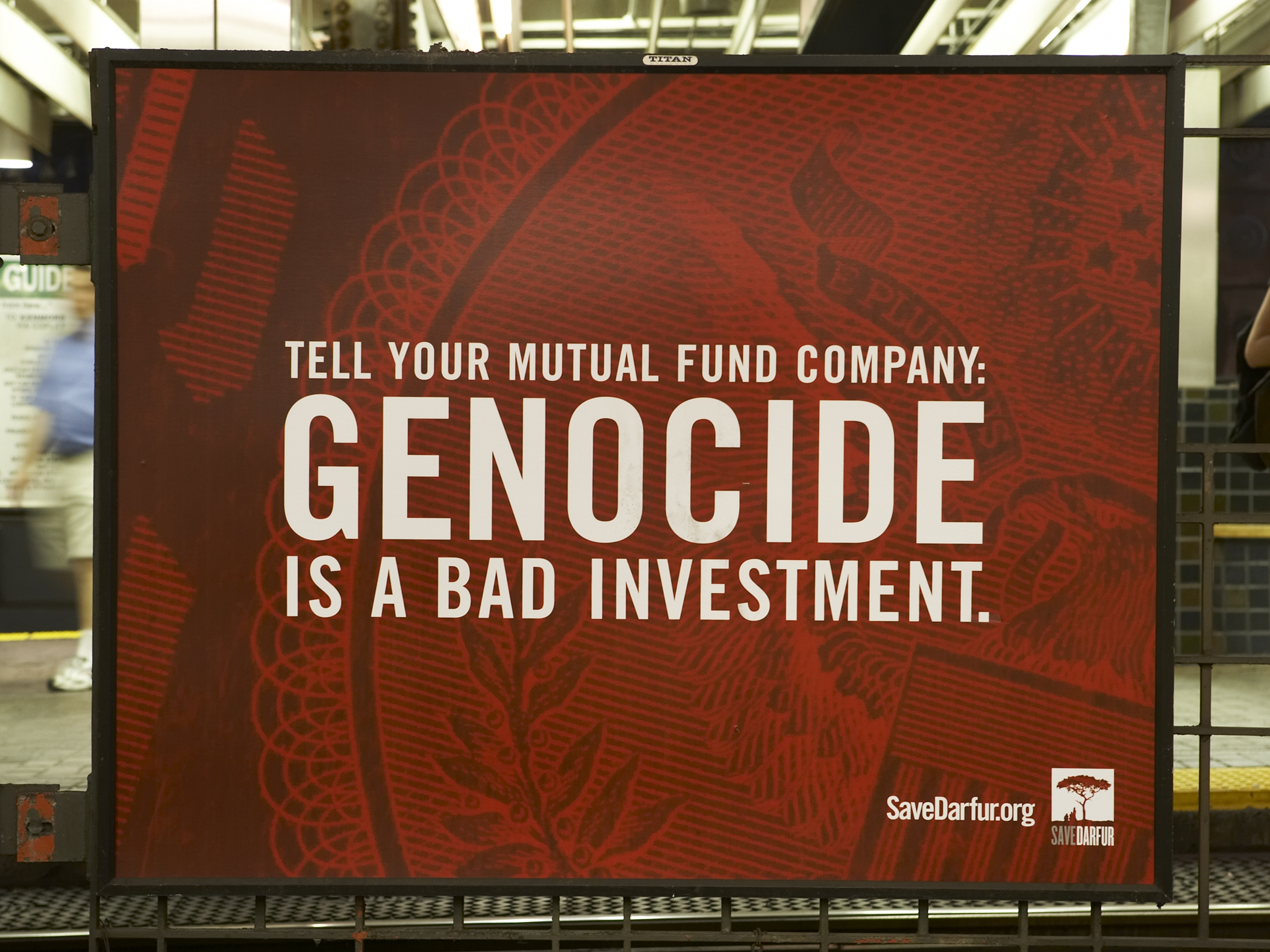

In May 2007 the Save Darfur Coalition opened a new front, launching a campaign to rally U.S. support for divestment from Sudan – encouraging individuals, states, universities and mutual funds to withdraw their investments from foreign companies whose dealings in Sudan were helping fuel the genocide. At the time, Fidelity Investments was the largest U.S. shareholder in PetroChina, which buys 60 to 70 percent of Sudanese oil. After repeated efforts to directly engage Fidelity were summarily rebuffed, Save Darfur decided to make an example of Fidelity. Overtures to their investment team had been met with cold, dismissive replies so we made those written replies public. To contrast Fidelity’s boilerplate language with the human tragedy on the ground, I traveled to a refugee camp in Chad to shoot TV and print ads featuring a young Darfuri woman with an actual letter from Fidelity.

Every refugee we spoke to had lost at least one member of their immediate family – no one escaped unharmed, and it made working in such adverse conditions seem trivial. It was a grueling production, but I would go back to Chad tomorrow if I could. It was the toughest and best experience of my career.

Fidelity caught wind of the impending publicity campaign and launched an effort to prevent the ads from ever running. Read about their efforts here. They and their lawyers were able to pressure a handful of media outlets not to run our ads, but we successfully secured placements in many national print publications and on local television in DC, New York and Boston – Fidelity’s hometown. To increase presence and pressure in Fidelity’s own backyard, we filled the subway station closest to their headquarters with more than 130 transit ads. Outside the station, volunteers distributed leaflets and answered questions from Boston commuters while mobile billboards circled the streets around Fidelity’s offices. Shortly after the campaign launched, Fidelity’s financial filings quietly revealed they had sold 91% of their PetroChina holdings. The campaign had received a great deal of press coverage, although Fidelity publicly denied having been influenced by our efforts.

After subsequent campaigns aimed at Berkshire Hathaway and Franklin Templeton Investments, we determined that awareness of Darfur and of the divestment issue had reached high enough levels that we could target individual investors. We created a national TV spot asking viewers to examine their own portfolios for holdings that could be inadvertently supporting the genocide. This was the first time we employed actors delivering scripted dialogue – a strategic shift we considered very carefully. I think this decision yielded one of the most memorable pieces of creative we produced for Save Darfur.

In less than five months, we helped the Save Darfur Coalition reach hundreds of millions of people across the U.S., Europe and the Arab world. During that time, the Coalition raised millions of dollars in donations and doubled its roster of volunteer activists from 400,000 to 800,000. Subsequent to our efforts, independent research found a substantial increase in awareness about the conflict, increasing from 14 to 60 percent the number of Americans who reported having heard ‘a lot’ about the conflict in Darfur. The survey found that nearly two in three Americans believed action to stop the genocide should be a high (42%) or the highest (19%) foreign policy priority of the United States. In a face-to-face meeting with emissaries from the U.S., representatives of the Sudanese government complained that our ads had “turned the world against them.” This remains one of the highest professional compliments I've ever received.

A change in leadership at Save Darfur brought with it a change in our role as well. Eventually, the Coalition moved away from advertising altogether and our working relationship ended. In my career, this is still the work of which I am proudest and yet I view it largely as a failure. While we met and exceeded our client’s expectations – garnering global attention and shaping the world’s opinion of a previously unknown conflict in a remote part of the world – we didn't put the Save Darfur Coalition out of business.